|

History of Markham

About 1000 AD, Markham was first settled by the Iroquois people who lived

in semi-permanent villages, growing mainly corn, but also squash, beans

and sunflowers, in the fertile soil they found in the valley of the river

they called the Katabokakonk, “river of easy entrance”. They also used the

river and valley as a route to the north country. In the 17th century,

five aboriginal tribes, speaking related languages—the Mohawk, Seneca,

Cayuga, Onondaga and Oneida peoples---formed a federation called the Five

Iroquois Nations.* The distinctive structure built by the Iroquois was the

“longhouse”, a grouping of these multi-family dwellings making up an

Iroquois settlement.

About 1000 AD, Markham was first settled by the Iroquois people who lived

in semi-permanent villages, growing mainly corn, but also squash, beans

and sunflowers, in the fertile soil they found in the valley of the river

they called the Katabokakonk, “river of easy entrance”. They also used the

river and valley as a route to the north country. In the 17th century,

five aboriginal tribes, speaking related languages—the Mohawk, Seneca,

Cayuga, Onondaga and Oneida peoples---formed a federation called the Five

Iroquois Nations.* The distinctive structure built by the Iroquois was the

“longhouse”, a grouping of these multi-family dwellings making up an

Iroquois settlement.

In 1608, the French founded a colony in Quebec City and,

from there, established settlements along the shores of the St. Lawrence

River. They began to explore further inland and laid claim to the lands

where Markham now stands. When they visited this area they found the

Katabokakonk river but, struck by how in places its waters were coloured

reddish by the clay along its banks, they named it the Rivière Rouge.

During these explorations, the French also pursued the fur trade with the

native peoples. In the middle of the 17th century, there existed a village

near the mouth of the Rouge River called Ganatsekwyagon, inhabited by

Senecas, one of the five nations of the Iroquois confederacy. It was

eventually abandoned but the discovery of relics at a location about a

kilometre up the eastern bank of the Rouge from Lake Ontario has lead to

the belief that it is the site of the village of Ganatsekwyagon.

With Britain’s victory in the Seven Years War with France

(1756-1763), the French King ceded his colony of New France to Britain.

This included the territory north of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie.

Britain now had to decide how to organize this new

territory. She created a province which she called Quebec and which

extended to just west of the Ottawa River. The territory to the west of

that line, including, of course, where Markham stands today, was

designated as Indian Territories. At first, new settlement was excluded

from this area and trade with the native peoples could be carried on only

under license. Treaties were negotiated with the aboriginal peoples.

In those years Britain was still in possession of her

American colonies located along the eastern seaboard of the Atlantic.

English-speaking peoples began to trickle into her new northern colony,

principally to Montreal or east. A decade after obtaining New France,

however, the difficulties for Britain of ruling a population that was

still predominantly French-speaking and Roman Catholic resulted in her

proclaiming the Quebec Act of 1774. This Act recognized the Roman Catholic

religion, and provided that in this territory the French Civil Code would

apply to civil matters, such as property, marriage and inheritance but

that in criminal matters the British criminal code would apply. The Act

also extended the boundaries of the territory called the “Province of

Quebec” westward to include where Markham stands today. It even extended

the boundary south to the Ohio River and west to the Mississippi.

The Quebec Act satisfied the French population but angered

the recent British arrivals who found themselves subject to laws which

they viewed as foreign. It also angered Britain’s American colonies who

coveted the lands that Britain had just included in the new boundaries of

the Quebec territory. The anger that the American colonists felt further

fuelled the already existing grievances that led to the outbreak of the

American war of independence in 1776.

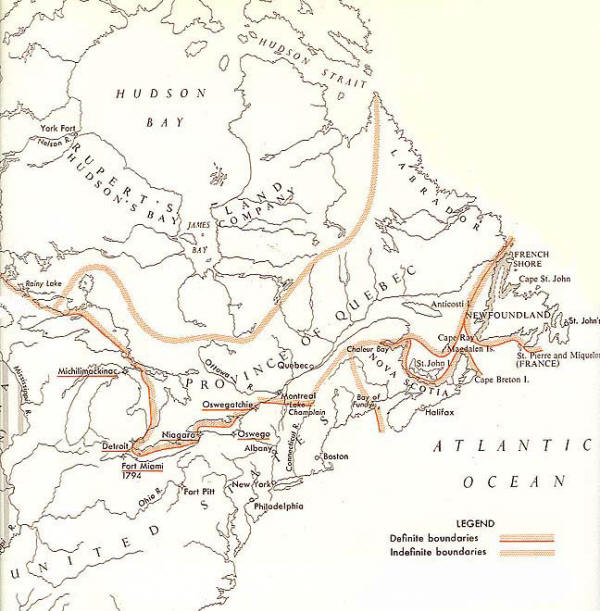

In 1783, Britain had to recognize the independence of the

new United States of America and from that year the western boundary

between this new country and Britain’s Province of Quebec was a line

running down the middle of Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, Lake Huron and Lake

Superior (see map below).

The American revolutionary war provoked a new immigration

north into British territory on the part of the United Empire loyalists,

Americans who left the fledgling United States to remain loyal to Britain.

Among them were also some German soldiers from among the foreign troops

that had been hired by Britain and brought over to reinforce its forces

fighting in the war. In 1787, with Loyalist settlements now established in

Niagara and others in Cataraqui (near Kingston) Governor Dorchester

negotiated a treaty with the Mississauga aboriginal nation in which the

Crown purchased a tract of land, called the “Toronto Purchase”, which made

it possible to connect these two settlements.

The arrival of the Loyalists, many of whom settled in the

western part of the Quebec territory, led the British Parliament in 1791

to pass the Constitutional Act that divided this territory into two

provinces, the eastern province to be called Lower Canada (corresponding

to the southern part of what is now the Canadian province of Quebec), and

the western part to be called Upper Canada (corresponding to the southern

part of what is now called the province of Ontario). In Lower Canada, the

French Civil Code would continue to apply, but in Upper Canada the British

Common Law would now apply to civil matters. Each province was to have its

own Lieutenant-Governor appointed by Great Britain, an elected Legislative

Assembly, and an upper house called the Legislative Council whose members

would be appointed by the Lieutenant-Governor.

The creation of the province of Upper Canada made it

possible for the settlement and development of our area to really take

off. The first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada was John Graves Simcoe.

During his term as Lieutenant-Governor, Simcoe took many steps which

impacted directly on Markham. The first capital of Upper Canada was

Niagara-on-the-Lake (then called Newark) but, located just across the

Niagara River from the United States, it was judged too vulnerable to

attack from the new American republic. Simcoe decided to move the capital

to York (now called Toronto).

For administrative purposes, Simcoe divided the province

into four districts which he named Eastern, Midland, Western and Home. The

districts were divided into counties, and the counties eventually into

townships. The Home District contained the provincial capital, York,

located within the wider county which was also named York.

One of Governor Simcoe’s greatest concerns was for the

military security of Upper Canada. The clearing of Yonge Street fit partly

into this strategy. Increasing the population by attracting new immigrants

through a system of free land grants was another important element. The

southern part of York was organized and surveyed into farm lots by 1792.

From 1793 to 1794 the same work was completed in the township of Markham.

Simcoe named the township after his friend William Markham, the Archbishop

of York (England) at the time.

An explanation of the system by which Markham township was

divided into lots gives us some clues to the emergence of the streets and

roads whose names are so familiar to us now. The township, rectangular in

shape, extended from Yonge Street to the Pickering Town Line and was

divided, from west to east, into ten sections, called concessions, each

one 1 ¼ miles in width. These concessions were bounded on the south by the

Scarborough Town Line (now called Steeles Avenue) and on the north by the

Whitchurch Town Line. They were crossed by a grid of six sideroads,

running east and west, which were also 1 ¼ miles apart. The land was

divided into 200 acre lots, running, long and narrow, from one concession

road to the next. On the north-south plane, five lots were created between

every two sideroads. The road we now call Highway 7 was originally called

sideroad 7 in Markham Township. The side road north of it is now called

16th Avenue. Some modern-day roads, however, still retain their original

names from the 1793-94 survey. For example, the 9th Line, on which is

situated the new community of Cornell, continues to be the name used for

an important north-south road in the eastern part of Markham.

This survey included the allocation of one seventh of the

lots to be reserved to support a Protestant clergy. These were called

clergy reserves. Another seventh of the lots were reserved for the

disposition of the Crown, in other words, of the Lieutenant-Governor’s

government. The fact that the Lieutenant-Governor could dispose of these

lands as he wished meant that he could raise money without having to ask

for the approval of the new local assembly. Remember that the

Lieutenant-Governor of that time had real power, which came, not from the

electorate, but from the powers conferred on him by the Imperial

Government in London, and he resented, and avoided when he could, any

constraints that an elected assembly could put on him. The Crown reserves

eventually were all sold by 1828 but the clergy reserves continued to be a

source of friction, and even contributed to the grievances which led to

the rebellion of 1837. They were not sold off until 1854.

But let’s return to the years immediately following the

creation of Upper Canada and the surveying of the new townships. European

settlement in Markham began with William Moll Berczy. He was a German

entrepreneur and artist who in 1792 led a group of German settlers to the

United States with the intention of settling in the Genesee Tract in upper

New York State. After their arrival in New York, however, problems arose

over land tenure and there were disputes over finances. The Berczy

settlers began to look elsewhere. In May of 1794, Berczy negotiated with

Simcoe for 64,000 acres in Markham Township, soon to be known as the

German Company Lands. The Berczy settlers, joined by several Pennsylvania

German families, set out for Upper Canada that same year.

Approximately a hundred and ninety arrived. The double

trials of harsh winters and crop failures made their first few years

difficult and a number of settlers moved back to Niagara, their first

point of entry into Upper Canada. Those who stayed were to eventually

prosper. Some of the Berczy settlers, using the Don River, moved their

equipment and provisions to lot 4 in Concession 3 where they founded a

small hamlet, complete with a grist mill for the grinding of grain, that

came to be called German Mills.

Another group of émigrés were French aristocrats who had

fled to Great Britain to escape the upheavals of the French Revolution.

They became a burden on the British government who, as a result, arranged

for their immigration to Upper Canada. Lots were set aside for them on

both sides of Yonge Street north of what later was called Elgin Mills and

in 1799 they arrived. This was not a group well suited to the rigours and

the isolation of what was still a remote area and eventually most of them

sold their holdings to one of their group who had been more successful,

Laurent Quetton St.

A very important immigration also came from the

Pennsylvian German communities of the United States. Sometimes referred to

as the Pennsylvania Dutch (partly due to an erroneous anglicization of

Pennsylvania Deutsch) these people had lived in Britain’s American

colonies for a century, their ancestors having left Europe to escape

religious persecution. But now, faced with a shortage of land for their

large families, and unwilling to swear allegiance to the new Republic,

some looked to the British territory to the north for new possibilities.

One of the members of this community who came to the Markham area to look

into land acquisition was Peter Reesor. He returned to Pennsylvania and

then, along with other families, came back in the trek of 1804. These new

settlers were able to purchase land at good prices. A hamlet grew up near

their settlements that was first called Reesorville, and later Markham

village. Unlike the Berczy settlers before them, they did not receive

their land as a grant. Because of their long experience in farming in

Pennsylvania, these settlers, most of them of the Mennonite religion,

adapted easily to their new country.

Although there was some immigration that came directly

from Britain, emigration to Canada via the United States was the main

source of new settlers for the first several years of the life of Upper

Canada, and of Markham in particular.

What kind of administration was in place at that time? The

four districts created by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe were the basic units.

In the Home District, as it was with the other three, the management of

local affairs was placed in the hands of magistrates who were appointed by

the Lieutenant Governor. The magistrates were responsible for all local

expenditures such as paying the fees for parish clerks and jailers,

appointing township and district constables, surveyors, and inspectors of

weights and measures. They also regulated markets, built and managed

courthouses, jails and asylums. Anyone who wanted a license to sell liquor

had to apply to the magistrates. The only ministers who could perform

marriages were those of the Anglican, Presbyterian and Lutheran churches

who had been licensed by a magistrate to do so.

The district magistrates were required to hold a yearly

town meeting at which local officers would be elected. A town meeting in

the Home District on July 17, 1797 records, among other appointments, the

naming of William Berczy as Overseer of Highways for the German Settlement

and John Stamm as its Constable.

In 1812, Upper and Lower Canada were in crisis as war

broke out between Britain and the United States. This was mainly the

result of trans-Atlantic issues between the two countries but, as the two

Canadas were British possessions, the United States attacked Britain

through her North American territories. Land invasions by the American

forces near Detroit and Niagara were both repulsed by a combination of

British regular forces, locally raised militias (in which some Markham

residents fought) and aboriginal fighters that rallied to the British

side.

These militias had come into existence due to the Militia

Act, a law that Simcoe had put through the Parliament of Upper Canada back

in 1793. This Act required all males between the ages of 16 and 50 years,

who were residents of Upper Canada and who were physically fit, to be

enrolled in local militia companies. These units had to muster and be

inspected twice a year. One unit of the local militia was called the York

Militia, in which John Button, from the 4th Concession Line of Markham,

held the rank of Captain. Captain Button was the first of three

generations of his family to serve in the Canadian militias, being

followed by Francis Button and William Button. Benjamin Milliken, after

whom one of Markham’s oldest communities is named, served as a private in

the York Militias. In 1813, American forces, backed by guns from naval

ships offshore, landed near Sunnyside beach, and occupied the town of York

for five days during which they burned the Parliament Buildings and

Governor’s residence and sacked many private homes that had been abandoned

by fleeing residents. Peace between Britain and the United States was

restored in 1814.

At the end of the Napoleonic wars, of which the war of

1812-14, was a side effect, Britain found herself with a large number of

demobilized soldiers. Many were attracted by the news of cheap land in

Canada. A number of ex-officers bought land along Yonge Street, while some

of the soldiers became pioneers, buying less expensive land further into

the township. Benjamin Thorne was one of these new settlers, operating a

mill in a spot that was called Thorne’s Hill, later abbreviated by the

Post Office to Thornhill.

During these early years of Markham’s history, when

pioneering, and its rigors, played the main role, there began also the

development of agricultural industries. The township’s many rivers and

streams soon supported water-powered saw, grist and woollen mills. In

fact, because of the poor roads, it was the presence of a local mill that

was usually the spur to the development of the first small hamlets. German

Mills, Almira, Buttonville (named after the family that took a leading

role in the militias) and Cedar Grove are examples of small hamlets that

developed around a mill site. Another of these hamlets, originally part of

the Berczy settlement, grew up at the 6th Concession Line just north of

the Rouge River, and took the name of Unionville after the re-uniting of

Upper and Lower Canada in 1841.

What were the events that led back to union? The

Constitution Act of 1791, that created the separate provinces of Upper and

Lower Canada and established the system of government that would prevail

in each, led to the rapid development of Upper Canada but it also

contained the seeds that grew into discontent and eventual rebellion. The

problem arose in that under the colonial governing structure the

Lieutenant-Governor was accountable mainly to the Imperial Government in

London, rather than to the elected assembly. He could appoint whomever he

wanted to public positions, including to the powerful Upper House of

Parliament, the Legislative Council. A small circle composed of the

Lieutenant-Governor, the members of the Legislative Council and a small

number of established families came to form a governing clique over whom

the people could not exercise control. This small but dominant group was

dubbed The Family Compact by William Lyon Mackenzie, the main spokesman

for those advocating a reform of the political system. The reformers

called for “responsible government”, a government that was responsible, or

answerable, to the elected legislature.

The people of Markham were typical of the province’s

population in that they were politically aware and the bitter

disagreements between the reformers led by Mackenzie and the citizens who

supported the Lieutenant-Governor created deep divisions. As part of the

riding of York, Markham elected MacKenzie as their member of the

Legislative Assembly on five occasions between 1828 and 1836 but he was

always expelled soon after. Many felt sympathy with his demands for

responsible government. But many of these sympathizers also continued to

feel loyalty to the Crown. Mackenzie, however, went beyond and began to

adopt openly republican views.

In 1837 armed rebellions broke out in both Upper and Lower

Canada. In Lower Canada, where the same grievances were fanned by a

French-Canadian national feeling pitted against a British-dominated

colonial regime, the uprising dragged on into the following year. In Upper

Canada, the revolt led by William Lyon Mackenzie, was quickly put down.

Mackenzie’s republican views had alienated some who could have been his

supporters. He was also no military strategist. However some Markham

farmers did answer the call to open rebellion, as a result, many faced

arrest. Other Markham citizens opposed the rebellion. Captain John Button

raised armed troops of militia to help to quash the uprising.

Although the rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada were

both defeated militarily, they did result in a major change to the way the

two provinces were governed. The British Government sent Lord Durham to

conduct an enquiry into the causes of the unrest. He recommended that

Upper and Lower Canada be reunited under a single government which would

be answerable to a single elected assembly. He also recommended that the

principal of Responsible Government be granted to this united province.

What that meant was that under the new constitution, the Governor, in all

matters internal to the province, could no longer act unilaterally, but

would conduct himself in the same way as the Queen did in the home

country. That is, he would govern on the advice of his elected ministers,

and his ministers had to enjoy the confidence of the elected assembly.

This is the principle by which we are governed today. One could say that,

through the granting of this principle in 1841, Britain ceased to govern

her colony of Canada as far as the purely internal affairs of the province

were concerned. This united province, however, did not become a sovereign

country. Our relations with other countries were still the exclusive

responsibility of the Imperial Government in London as was, to a large

extent, our defence.

Under the old constitution, and the new, electoral

politics remained a rough affair. Voters had to travel long distances, and

at the polling locations they voted verbally. There were often attempts

made to intimidate voters. Free liquor was offered in the taverns during

election week.

Drinking was itself an issue much debated in those times.

Because of the difficulty of transporting grain, local breweries sprang up

in many communities. For innkeepers, the sale of liquor was the basis of

their livelihood. At harvesting, barn raisings—and other tasks where many

pitched in---alcoholic drinks were generally expected to be provided. As

the years passed, the temperance movement gathered strength in response to

this and the contention between the two sides was ongoing.

The new system of responsible government also greatly

reduced the privileged position of the Church of England, or Anglicans.

Under the previous regime, centred as it was around the British appointed

Lieutenant-Governor, the Anglicans had been favoured. The clergy reserves

set aside in the land survey had been for their benefit. Until 1831 the

only Protestant denominations allowed to perform marriages were, most

importantly, the Anglicans, and, in addition, Lutherans and Quakers. Some

smaller and newer sects, such as the Methodists, were starting, however,

to gain followers. The Methodists were distinguished by their use of the

itinerant preacher, who rode on horseback, or, in winter, by sleigh, to

visit believers.

Another change that came as a result of responsible

government was that more public money was invested in education. In

Markham’s early years, with the arrival of the Berczy settlers and the

Pennsylvania Germans, Markham as a community had a distinctly German

character. Many of the schools in those communities used German as the

language of instruction. Later, in 1844, Dr. Egerton Ryerson was appointed

to organize the school system in Canada West, the western half of the

United Province of Canada. Starting in 1849, municipal councils could levy

taxes specifically for school purposes and Markham Township appointed

Anglican Rev. George Hill as its first supervisor of schools. The most

common in those days was the one room elementary school, in which one

teacher taught all the grades. By 1870, all school expenses were paid

through taxation and school attendance was compulsory for children aged 7

through 13. They had to attend school at least 100 days every year.

The Municipal Corporations Act of 1849 affected more than

just the school system. It went a long way toward bringing our system of

local government closer to what we experience today. In 1841 the old

District town meeting had been abolished and replaced by an elected

District Council but this proved to be only an interim stage. The 1849 Act

abolished the District system completely and established municipal

governments to replace it. The county became the unit of organization, and

county and township councils were established. In 1850 by-laws were passed

by which the Township of Markham would be regulated and in 1851 David

Reesor was elected Reeve. Henry Miller became deputy Reeve and there were

three Councillors.

In Markham, by the middle of the century, most of the

township had been cleared of forest and much of the land was under

cultivation. But maintaining the concession lines and side roads was

always a challenge. Most of the work was done by statute labour. The farm

owners were obligated, according to their assessment, to provide a certain

number of days of work on the roads, including the supplying of a team of

horses and a wagon. One early method of dealing with swampy ground was the

laying of tree trunks side by side. Earth was dug from the side of the

road and laid on top of the logs. This also produced a ditch on each side.

However, with rains and floods, the earth covering was washed away and

these so-called “corduroy” roads became bone jarringly bumpy. Paving the

main roads by laying successive layers of broken stone (this was called

macadamizing) proved too costly, with the result that they were planked

instead. That, however, was not an ideal solution either as the planks

heaved, broke or wore out and needed to be replaced every eight years. In

1864 gravelling was adopted as a means of maintaining some of the main

concession lines and side roads. Over time, the population increased and

villages like Thornhill, Unionville and Markham greatly expanded.

Specialised industries began to spring up, such as wagon works, tanneries,

farm implement manufacturers and furniture factories.

The road that was critical to the development of all the

communities along its path was Yonge Street. When Lieutenant-Governor

Simcoe decided on Toronto as the navel arsenal of Lake Ontario, he looked

for the most direct route north from Toronto to Georgian Bay and Lake

Huron. He decided that following the old Indian trail to Lake Simcoe, and

then using the system of rivers and portages from there, was the best

route. Surveying of this road began in 1794 and the road was named Yonge

Street by Gov. Simcoe after Sir George Yonge who was then the Imperial

Secretary of War. The cutting out of the road to Lake Simcoe was completed

in 1796. William Berczy helped with the work on the road, starting at

Eglinton, by sending a crew of men from the Berczy settlement. As the

years passed, the road was used by settlers, fur traders, and also by

detachments of soldiers making their way to the military base at

Penetanguishene on Georgian Bay. The road was surveyed into farm lots on

both sides from Eglinton to Holland Landing, traversing several townships,

including the Township of Markham. Settlers along Yonge Street, as

elsewhere, had to clear ten acres for cultivation and fence it, build a

house 16 by 20 feet, and cut down all trees on the front of the lot. As

the use of the road increased, inns began to be established, and some

small companies providing transit, by horse drawn coach, began to operate

along Yonge Street.

In 1867, Canada’s constitution changed again. We mustn’t

forget that until that year the term Canada applied only to the territory

on both sides of the St. Lawrence River and to the north of Lake Ontario

and Lake Erie. In 1864, Canada began negotiations with the British

colonies in the Maritimes and, after three years of talks, came to an

agreement with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to form a federal union, each

retaining a provincial government and elected assembly, and with a federal

capital and parliament located in Ottawa. This was called Confederation.

The new larger entity would also be called Canada and its first prime

minister was Sir John A. Macdonald. The terms of the union also involved

dividing the old province of Canada into two again, one called Quebec, and

the other Ontario, each also with its own provincial government

responsible to a locally elected assembly. But this new, and bigger,

Canada was still a colony within the British Empire. We had internal

self-government and Britain expected us to be responsible for forming a

militia for our own defence but Britain maintained a navy base at Halifax

and still handled our relations with other countries.

Toronto became the provincial capital of Ontario. Railways

had already made their first appearance in 1853 with the inauguration of

the Ontario Simcoe and Huron Railway. The development of railways in

neighbouring townships posed a challenge to Markham’s own prosperity, so

local business owners began to look for allies who could form a railway.

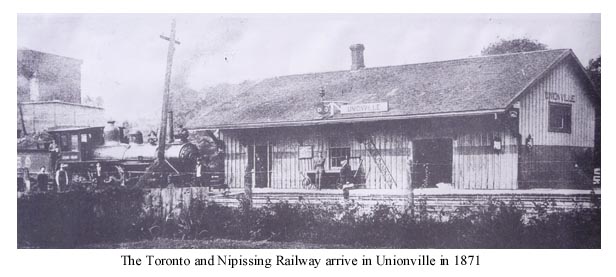

On September 14, 1871, the Toronto and Nipissing Railway Company, with

stations in Unionville, Markham and Stouffville, officially opened its

Scarborough-Uxbridge line.

At first the railway brought

renewed prosperity and rapid development. Increased communication with

Toronto, however, brought about many changes. In 1896 the Metropolitan

Radial Railway was opened up. This made travel from Toronto to the

northern communities along the Yonge Street corridor much easier and the

era of coaches and inns eventually came to a close. An interesting

footnote to the impact of the new Radial Railway was that some artists who

later became members or supporters of the Group of Seven moved from

downtown Toronto and came to live in Thornhill, or to visit it frequently.

One member of this group was J.E.H. MacDonald. Added to the railway links

were also improved connections through telegraph and telephone, all of

which eventually diminished the industrial role of the villages in the

Township of Markham after the turn of the century.

Most of the communities within the Township of Markham

looked to the Township Council for local services. However some villages

grew to a size that entitled them to seek incorporation, giving them more

local authority. In the old Ontario system of municipal government, there

were police villages, villages, towns and cities. When a population of at

least 750 was found within an area of 500 acres, it could apply to be

incorporated as a village, a status that gave it some measure of

self-government. A smaller population gathered in one centre could be

organized as a police village having less local authority than a village.

When a village attained a population of 2,000 persons it could be

incorporated as a town with larger powers. Finally when a town reached a

population of 15,000 it could be incorporated as a city with still more

extensive powers.

Markham Village, its growth further spurred by the opening

of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway in 1871, was incorporated as a

village in 1873. By 1900 it had a population of 950 people and boasted an

impressive new Town Hall. Just to the north, the community of Mount Joy

became a police village in 1907 but in 1915 was annexed to Markham

Village. Unionville was another of the stops of the Toronto and Nipissing

Railway. This contributed to the growth of the community and in 1907

Unionville attained the status of police village.

The growth of centres of population did not always

strictly follow the township boundary lines and three villages in

particular grew up that straddled the lines between two townships. In the

northeast, Stouffville was located along the border between Markham and

Whitchurch townships. Like Unionville and Markham villages, it lay along

the route of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway but being more distant from

Toronto, it developed more independently and in 1873 was incorporated as a

village. Along Yonge Street two villages grew up whose developments were

greatly linked with this important road. Thornhill expanded, with its

eastern part in Markham Township and western part in Vaughan. It attained

status as a police village in 1931. This led to arrangements such as

having its fire protection provided by the two townships but paid for by

the village. Further north, Richmond Hill also straddled Yonge Street, and

thus also lay within both Markham and Vaughan townships. It was

incorporated as a village in 1872.

The advent of the automobile, following the arrival of the

railways, went further in making it difficult for local industries to

compete with the larger factories in Toronto. As a result, Markham

Township, which had once been called the Birmingham of Canada, slowly

returned to its old identity as a quietly productive agricultural

community.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 and Canada’s

participation in the war effort spurred Canada’s evolution toward full

sovereignty. As a member of the British Empire, Canada was automatically

at war when Britain declared war on Germany and Austria. Canadian

soldiers, under ultimate British command, fought in many key battles. One

of them was fought at Vimy Ridge, France in 1917. The 90th anniversary of

this battle was recently commemorated. When the war was over the feeling

had grown among Canadians that it was time for them to decide for

themselves what their relationship with the rest of the world would be.

Canadians did not wish any longer to be automatically at war when Britain

was at war. Canada took on responsibility for its own diplomacy and in so

doing assumed status as a fully sovereign country.

The war also had an impact on the life of Markham. Still

mainly agricultural, Markham was affected by the departure of many of her

young people to fight in Europe. The shortage of labour stimulated further

the trend toward mechanization on the farm. The development of farm

machinery such as the grain combine meant that communal tasks, such as the

threshing of grain, were no longer necessary.

After World War II (1939 – 1945), however, Markham began

to feel the effects of urban expansion from Toronto. Heavily

industrialised by the war effort and experiencing a post-war baby boom,

the population of the township grew. Markham Township celebrated its

centennial as a municipality in 1950 and rapid change was in store. It

became the destination for waves of new immigrants from all over the

world, but especially from people from the war ravaged countries of

Europe.

In 1971, the modern Town of Markham was created, a single

town now absorbing the former villages of Unionville and Markham and most

of the territory of the old Township of Markham. But the new town did not

correspond exactly to the old Township rectangle. Some of the western part

was annexed to the new Town of Richmond Hill and the northern boundary was

moved south to a line between 19th Avenue and Stouffville Road, leaving

the village of Stouffville entirely in the new Town of

Whitchurch-Stouffville. The Police Village of Thornhill was dissolved and

this community was split along Yonge Street between the Town of Markham

and the City of Vaughan. The citizens of the new Town of Markham now elect

a Mayor, and a Town Council made up of Councillors from the eight town

wards and four Regional Councillors.

What are the duties of a “Regional Councillor”?. The

reorganization of 1971 also created the Regional Municipality of York,

made up of the city of Vaughan, the towns of Markham, Richmond Hill,

Whitchurch-Stouffville, Newmarket, Aurora, East Gwillimbury and Georgina,

and the township of King. This municipal federation provides services that

are best provided across the entire region rather than by each town on its

own. These include a police force, a regional public transit system and a

common school board. Thus, Markham voters, in addition to the eight Town

Councillors, also elect four Regional Councillors who, along with the

Mayor, represent Markham on York Regional Council which has its seat in

Newmarket. Markham’s four Regional Councillors also sit on Markham’s own

Town Council.

The opening of Highway 404 in the mid-1970s further

accelerated the urban development of the town. Markham has attracted many

companies of the high technology sector and now styles itself the “High

Tech Capital of Canada”.

The growth of the population along with the arrival of new

industries has resulted in large acres of farmland being turned to

subdivisions and industrial areas. Markham now increasingly confronts the

often conflicting needs of urbanization and preservation of natural

spaces.

Since its very beginnings, Markham’s progress has been

stimulated by immigration and the city has in recent years attracted a

new, dynamic and multicultural population with roots in every continent.

Especially significant in the last quarter century has been immigration

from Asia, with almost thirty per cent of Markham’s current population of

287,000 being of Chinese origin, and twenty percent from South Asia.

New and exciting pages in Markham’s history are being

written today but amidst the rapid change and growth the old rural

beginnings of Markham are still there to be seen and enjoyed by all.

|