|

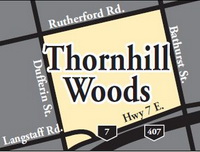

The growth and development of Thornhill is directly

related to several geographical factors, namely, the development of Yonge

Street as an important transportation route, the Don River system running

through the village, and lastly, Thornhill's proximity to Toronto.

Thornhill is divided in half between the Town of Markham

and the City of Vaughan, and runs along both the east and the west sides of

Yonge Street. The first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves

Simcoe, first developed Yonge Street as a military road. His initial

attempt at trying to find a north- bound route from Fort York (Toronto)

along the Carrying Place Trail was considered a failure.

The Carrying Place Trail was an aboriginal route to

Georgian Bay along the Humber River system. Simcoe explored this route

in 1792, but found it very difficult and long to travel. On the way back

from this trip, a guide showed him a less known aboriginal route. The

trail connected Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe from York (Toronto). A

year later Simcoe instructed Augustus Jones to survey the trail system that

was to be named Yonge Street. (Yonge Street was named after Simcoe's friend

and Minister of War, Sir George Yonge.) By 1793, William Berczy, had

cleared the trail as far as the present site of Thornhill. Later that

same year a group of soldiers, the Queen's Rangers, were dispatched by

Simcoe to finish the road to Holland Landing (Lake Simcoe). Yonge

Street, the longest road in Canada, was finally completed in January 1794.

In 1792, Simcoe announced a plan to attract settlers to

Upper Canada (Ontario). The plan offered 200 acres of land to pioneer

settlers, provided they undertake certain duties in return. Settlers

had to clear and fence 10 acres of grant land, erect a dwelling, and clear

33 feet of land across the front of the property for a road. This work

was to be completed within two years of settlement. By 1800, all the

lots between what is now Steeles Avenue and Langstaff Road were granted to

prospective settlers. Simcoe's policies would populate and develop

communities throughout Upper Canada.

In the early 19th century, water was the main

source of power that drove industrial machinery. Thus the Don River

played an important role in the early development of Thornhill. It

provided power for saw and gristmills (flourmills) that were established in

the area by the new settlers. These mills helped produce lumber to build

homes and flour to help produce staple foods such as bread and other baked

goods.

The earliest settlers were either United Empire Loyalists

or Americans taking advantage of the generous terms of Simcoe's settlement

offer. In 1801, Jeremiah Atkinson built the first major saw mill on

the Don, west of Yonge Street in Thornhill. A gristmill was

constructed in 1802 and gradually, as a result of the mill, the first signs

of urban settlement began to emerge.

The years following the War of 1812 saw another wave of

immigration take place. The end of the Napoleonic Wars was

characterized by significant social and economic change in Great Britain.

The result was a period of emigration of upper class families, newly

impoverished by the upheaval, and of servicemen seeking to start a new life.

Of particular importance was the arrival of Benjamin

Thorne in 1820. Thorne set up a warehouse in York dealing in the

export of grain and import of iron. When William Purdy's Mill burnt down,

Thorne purchased the remains and erected a larger gristmill. By 1830,

Thorne was operating a gristmill, a sawmill, and a tannery. The small

settlement came to be known as Thorne's Mills and then Thorne's Hill after

Benjamin Thorne.

In 1828, Thorne and his brother-in-law, William Parson,

petitioned the government for a post office. It was granted in 1829

and the village was officially called Thornhill, with Mr. Parson being its

first postmaster. Thorne became the major influence in the economic

life of the village.

A variety of industries, services and artisans had

located in Thornhill by the year 1830. Included among them were two

sawmills, a distillery, several blacksmiths and harness makers, two inns, a

millwright, a stonemason, a tanner, a weaver, a wheelwright, and a

shopkeeper. (A first account look at Thornhill during this period can

be found in the diary recordings of Mary Gapper O'Brien, published as "The

Journals of Mary O'Brien".)

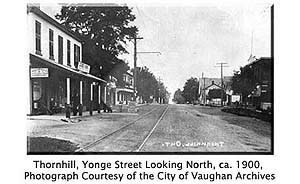

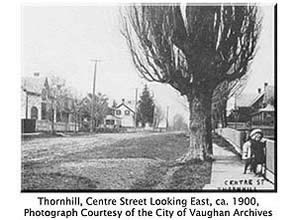

Between the years 1830 and 1848, Thornhill experienced a

period of sustained growth and prosperity. The business district of

Thornhill developed on Yonge Street in an area between Centre Street and

John Street. Stagecoaches traveled between Holland Landing (Lake

Simcoe) and York (Toronto) as Yonge Street's road conditions improved with

new grading and stonework. During this prosperous period, many of the

old churches, which survive today, were constructed. Included among

these were Trinity Church (now Holy Trinity), built in 1830 and moved to

Brooke Street in 1950; the British Methodist Church on Yonge Street, which

was built in 1838 and moved to Centre Street in 1852 was partially destroyed

by fire in 1983.

Agriculture prospered during this period as local farmers

took advantage of the new mechanical advances, such as reapers and

threshers. In addition, the millers found a ready market for their

products in the protected British market. The village came to acquire

further services and the original Crown lots were subdivided to provide for

the needs of the new urban class. By 1848, Thornhill was the largest

community on Yonge Street north of Toronto, having a population of

approximately 700 people.

Thornhill had grown into a bustling, milling centre by

the mid-1840s. However, the factors that fostered its growth, namely

government policy, economics, and technology, all evolved and changed around

mid-century resulting in an extended period of stagnation. Foremost of

these changes was the British Government's repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846,

which ended lower import tariffs for Canadian grain into the British

markets. Farmers and millers were left with a glut of surplus grain.

So serious was the oversupply that Benjamin Thorne was left with large

amounts of wheat with no market. As a result, he went bankrupt.

In 1848, the distressed Mr. Thorne committed suicide soon after selling his

asset and satisfying his creditors. This was the first of a long

series of events that eroded the economic base of the village.

The decline in milling continued into the latter part of

the 19th century as less lumber was required for construction and

was available for milling. Agriculture was also in a state of flux by

the mid-1870s. Farmers to protect themselves against fluctuating grain

prices, began to engage in mixed farming, much to the disadvantage of the

flour millers whose services were required less and less. This

economic downturn was further exacerbated by the decline of soil fertility,

which contributed to reduced grain yields. Floods destroyed many of

the remaining sawmills and fire took its toll of the gristmills. By

1885, most mills had disappeared or had been replaced by steam-powered

operations.

By the mid-19th century, steam had replaced waterpower as the

main source of energy used in industry. Transportation was

particularly affected as the railroad tracks began to cross the countryside.

Communities sought to have the tracks run through their villages to take

advantage of the benefits the trains would bring. Thornhill, however, was

by-passed, thus losing a potential source of growth. In 1853, the

Ontario Simcoe and Huron Railway was constructed through Concord.

By the end of the 19th century, Thornhill had become primarily a

service centre for the surrounding farmland.

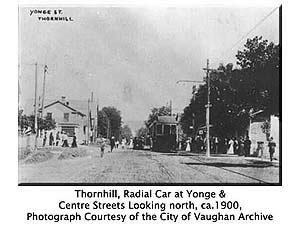

In 1896, the new mode of transportation, the Metropolitan

Radial Railway (bus-like cabins on rails) reached Thornhill, bringing

commuters to and from Toronto.

Prior to that time, the only public transit

to the city was a three hour ride by stage coach.

The electric street railway was a significant improvement

in both speed and convenience and for the first time, it was possible to

live in Thornhill and work in Toronto. By the late 1920s, the

automobile became a

popular source of transportation for many people,

further facilitating travel on Yonge Street.

Growth, however, remained slow until after World War I,

when several subdivisions were registered in the area and Thornhill acquired

its three golf courses: Uplands, Thornhill and Toronto Ladies. Much of

the subdivision activity in this period was speculative in nature and not

developed until after World War II.

During the early part of the 20th century, Thornhill was home to

several Group of Seven artists. J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Fred

Varley, Franz Johnston and Frank Carmichael all lived in Thornhill in the

1920s enjoying and painting the rural beauty of Thornhill.

In 1931, Thornhill became a Police Village. Until that

time, Thornhill had been a postal area with no independent municipal status.

Thornhill had been split between the then Townships of Markham and Vaughan

along Yonge Street since the initiation of municipal government in 1850.

Each Township administering their half of the village. The creation of

the Police Village gave Thornhill its own political boundaries.

Three elected trustees administered the village at this time.

The full effect of commuters and the northward growth of

Toronto were not felt in Thornhill until the years after World War II.

Existing subdivisions were completed and new ones registered as post-war

prosperity and the automobile brought families into the suburbs.

On January 1st, 1971, the Regional

Municipality of York Act came into effect, adopting the Metropolitan system

of government. With the creation of a regional government administration,

the Police Village of Thornhill ceased to exist and the administration of

the community reverted back to the newly created Towns of Markham and

Vaughan.

Today, Thornhill is a large urban community with over 49

thousands residents. Its ethnic composition is very diverse with a

large Jewish, Eastern European and Italian population. It is a

community that has grown expansively from its early beginnings, reaching

north to Richmond Hill and south to Toronto. Its residents enjoy all modern

amenities for shopping, recreational activities, schools, libraries and

other conveniences.

|